|

(Chapter VI, section 5)

What the Kelts were to western Europe, the Scythians and their relatives became, at about the same time, to the treeless plains to the east. Riding astride, wearing trousers, and sleeping in covered wagons, they spread rapidly over the grasslands of eastern Europe and western central Asia, shifting so adroitly that Darius with his army could not catch them, and disappearing almost as rapidly from the face of eastern Europe as they had appeared. Like the Kelts, they were both dazzling and ephemeral. But unlike the Kelts, their way of living, perfectly adapted to the grass-lands on which they roamed, was destined long to survive their identity as a people. About 700 B.C. the Scyths were first noticed in the lands to the north of the Black Sea.56 Their domain reached from north of the Danube and east of the Carpathians across the fertile plains of eastern central Europe and southern Russia to the River Don. From this country they were supposed to have ousted the somewhat mysterious Cimmerians. Although the Don formed their eastern boundary, beyond it lived other groups of nomadic peoples culturally similar to the Scythians. These included the Sarmatians, their immediate neighbors to the east, who were, according to Herodotus, the result of a mass marriage of Scythian youths and Amazon maidens. The speech of the Sarmatians was said to be somewhat different from that of the Scythians, owing to the inclusion of Amazon words and an Amazonian manner of pronunciation. Beyond the Sarmatians lived the Massagetae, and beyond them the Saka. The word Saka, however, was used by the Persians as a general term, to include all of the nomadic peoples to the north of the Iranian plateau, in the two Turkestans. In costume, in weapons, in methods of transportation, in living quarters, and in the totality of material culture, these people formed a continuous cultural zone from the Carpathians to China. It has been the custom to consider the Scythians a people of Asiatic origin who developed this high and specialized form of pastoral nomadism in central Asia and brought it with them to eastern Europe. Proponents of this school have suggested that the Scythians were a mongoloid people, and that they employed some Altaic form of speech. Another school holds that they were European in physical type, and spoke Iranian, while their cultural breeding ground lay somewhere to the east of the Caspian. We do not know what language the Scythians spoke, nor is it likely that its exact affiliation will ever be definitely established. Their geographical position, however, and their association with the ancient Persians, makes the Iranian hypothesis very likely. This theory is further strengthened by the study of the language of the Ossetes, a living people of the Caucasus, who are supposed, on historical grounds, to be descendants of the Alans, a branch of the Sarmatians. Their language is definitely Iranian. Although the general manner of living enjoyed by the Scythians does resemble in a remarkable degree that of the later Huns, Turks, and Mongols, one looks in vain for some of the cultural traits of these later Altaic speakers which may be ascribed to a relatively recent Siberian origin. These include the yurt or collapsible felt-domed house, and the Turko-Mongol type of shamanism. The Turks and the Mongols, without question, took over almost completely the whole Scythian style of culture, but they added to it elements of their own which reflected their former habitat and manner of life. A few traits connect the Scythfans with their neighbors to the north, the Finns; among these might be cited the sweat bath. The Scythians proper possessed a type of feudal organization headed by a king, who ruled over four provinces each of which had local governors; These Scythian kings were all buried in a royal burial ground in the region called by the Greeks the Land of the Gerrhi, which was situated in the bend of the Dnieper River near Nicopol. No matter where the Scythian monarch died, his remains would be deposited, in a funeral chamber, with great ceremony and with an extravagant quantity of human sacrifice, underneath a huge mound erected for that purpose. The richness of the burials, and the wholesale suttee, are reminiscent of the ancient Sumerians, and of the early Egyptians. The eventual Sumerian origin of this Scythian custom is not unlikely. This region of the Royal Scythian burying round has been a source of great activity for both treasure hunters and archaeologists. The Scythians had a definite idea that this was the place in which their kings were naturally at home, and while it may not be wise to stress this point too much, it would seem that this location may have reflected their notions as to their original dwelling place, or at least that of their royal clan. Similarly, the Mongols in later times buried their dead in a restricted area in the Altai Mountains, which they considered holy ground. During the first century B.C., the Sarmatians penetrated westward, crossing the Don, and driving the Scythians from their former homes. About 200 A.D., the Goths took the Scythian country from the Sarmatians, and in turn adopted much of the Scytho-Sarmatian culture, becoming great horsemen and learning to live in wagons. The Alans were the only branch of the Sarmatians to retain their integrity in face of this Germanic onslaught. They built up a great kingdom between the Don and the Volga, reaching as far as the Caucasus, including in it most of northwestern Turkestan. Between 350 and 374 A.D., the Huns destroyed the Alan kingdom. Some of the Alans went westward with the Huns, others accompanied the Vandals to North Africa, and a few, as previously mentioned, survive in the Caucasus as Ossetes. Although these Iranians (if the Scythians and Sarmatians really were Iranians) were replaced by Altaic speakers in southern Russia, and throughout the breadth of their Asiatic domain, this process took some time, and Iranian languages clung on for a long while in Kashgaria and in the oases of Russian Turkestan. Undoubtedly, the Scythians and their relatives were not destroyed, but were absorbed and reinccrporated. In studying the racial type of the Scythians, one must remember that they were not considered a homogeneous group by Herodotus, who is our chief historical source. They consisted of an inner clan called the Royal Scyths or True Scyths, who were the nobles and leaders, and, as a second element, the whole group of nomadic tribes of which the Royal Scyths were the integrating force. Herodotus also makes it clear that the Scythians kept many slaves. Only the Royal Scyths refused to own slaves, but employed youths of pure Scythian blood as bodyguards, and sacrificed these |

|

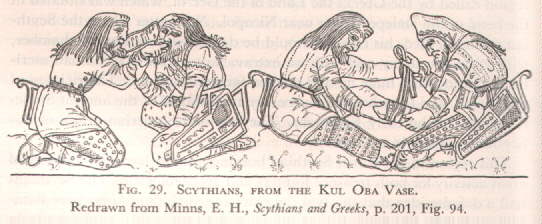

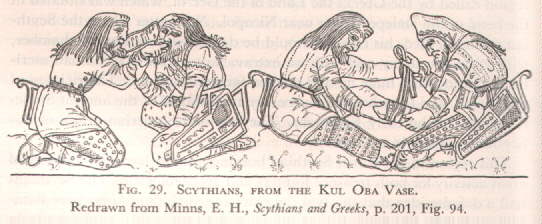

in their tombs. Thus, the Royal Scythian burial mounds must contain a relatively pure Scythian group. One must not imagine that the Scyths and their slaves were the only inhabitants of southeastern Europe during the last seven centuries before Christ and the first two of our era. Herodotus mentions the agricultural Scythians, who were probably some earlier sedentary people or peoples who remained as underlings of the Scythians and their providers of cereal food. We must remember that much of the Scythian territory had been farmed as early as Neolithic times. There can be little doubt, even before examining the skeletal evidence, that the Scythians and Sarmatians were basically if not entirely white men and in no sense mongoloid. The only definite description of them which we have from classical literature is that of Hippocrates, who called them white-skinned and obese, but this designation was employed by the father of medicine to prove one of his environmental theories. In later times, the Alans are described as having golden hair. Fortunately, we are not limited to literary references. The Scythians themselves, under the influence of powerful Greek colonies on the north shore of the Black Sea, and particularly in the Crimea, produced a dis tinctive style of realistic art in gold repoussée. These tepresentations in-clude a number of portraits of Scythians in very realistic and life-like poses. They show a well-defined type of heavily bearded, long-haired men with prominent, often convex, noses. The browridges are moderately heavy, the eyes deep set. These faces are strikingly reminiscent of types common among northwest Europeans today, in strong contrast to those shown in the art of the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Hittites, which are definitely Near Eastern. The face, therefore, is definitely Nordic, while the body build looks often thick-set and very muscular, but this may be due to the clothing, which includes baggy trousers and jackets with full sleeves. The pointed caps which they wear and the long hair make it impossible to form a useful opinion of their head form, but this is unnecessary, since we may soon discover it from reference to the cranial material. Persian representations of Saka show exactly the same type, depicted by the followers of an entirely different school of art, and hence this type cannot have been an unfounded convention. There is, in the anthropometric literature, sufficient data to permit the reconstruction of the Scytho-Sarmatian cranial type or types. The most extensive group, and that which may be used as a basic series, is Donici's collection of seventy-seven Scythian crania from kurgans of Bessarabia, which was one of the favored Scythian pasture lands during the height of their domination.57 (See Appendix I, cot 37.) The fifty-seven male crania of this series are not homogeneous, but fall into two types, a long-headed and a round-headed, with the former greatly in the majority. The means of these Scythian skulls show them to be low mesocephals of moderate cranial dimensions, but with a low vault height. The cranial means are, in fact, almost identical with those of the Keltic series from France and the British Isles. They resemble the Aunjetitz and Hallstatt skulls only as much as the Keltic series mentioned resemble these latter. They are, furthermore, metrically identical with the previously studied skulls from the Minussinsk region of southern Siberia, which may have been contemporaneous with them. One of the peculiarities of the Scythian skulls is a low mesene upper facial index, lower than that of the Kelts or of the Minussinsk people. Donici has shown, however, that this low upper facial index is mostly associated with the brachycephalic element in the group, and the same is true of many of the chamaeconch and mesorrhine skulls. When the brachycephalic element is eliminated, therefore, one finds these skulls to be narrower faced, and narrower nosed, and to fit more nearly into a central European Nordic category. Other series of Scythian crania from southern Russia and from the Caucasus show the same general characteristics as that of Donici's type series, but are in most cases purely dolichocephalic, which leads one to suppose that the brachycephalic element in the Rumanian skulls may have been at least partly of local origin.58 Other collections of Scythian crania vary in their mean cranial indices from 72 to 77. Those from the Kiev government, a Scythian center, have a mean of 7359 A series of eighteen Sarmatian crania from the Volga, although otherwise the same as the others, has a cranial index of 80.3.60 However, one hesitates to consider this typical of the Sarmatians as a whole, since both the Alans61 and the early Ossetes62 were long headed. The former preserved the original Scythian Nordic type until the ninth century A.D. Of especial interest is a rich kurgan in the Royal Scythian burial district,63 near Alexandropol; this was one of the most imposing kurgans of Russia, not only for its size but for the quantities of gold placed with the dead king, and of animals sacrificed for his convenience. The kurgan contained five skulls in the primary interment; one of these was a large male of Corded type.64 Another is a brachycephal with a vault especially wide behind, with a broad face and a narrow nose, resembling a Turkish or perhaps a Bell Beaker type; two are narrow skulls of the normal Scythian Nordic variety, while the fifth, that which occupied the king's chamber, is of moderate size, long headed, with a low vault, sloping forehead, a high, prominent nose, and wide flaring zygomatic arches. The malars are large, and there is, in this respect, a slight mongoloid suggestion. One may not, however, on this evidence alone, identify the Royal Clan with Turks or Mongols. We know very little of the stature of the Scythians. Nine male skeletons from the Polish Ukraine, associated with crania of standard Scythian type, have a mean of over 170 cm.65 It is tempting to find the origin of the Scythians in the previous population of the southern Russian plain. A series of Bronze Age crania from the lower Volga region is identical, at least in indices, with the later Scythian group, and so is that from the Ukrainian Urnfields. Three skulls of so-called "Cimmerians" likewise show no important deviation.66 Furthermore, an important series of Early Iron Age crania from the Sevan district of Armenia, probably dated from the earlier half of the first millennium B.C., and probably therefore earlier than the Scyths in Europe, or at least as early as their first appearance, is exactly like the more dolichocephalic element in the Scythian group, and manifestly Nordic. The vault, like that of the Scyths, is low, the nose leptorrhine, the face leptene, with more compressed zygomata.67 (See Appendix I col. 38.) Morphologically, these Armenian skulls are characterized by a medium forehead slope, moderate browridges and muscular development; a moderately deep nasion depression, and straight or lightly convex nasal profile; a projection of the occiput which is most marked in the lower segment, and accompanied by some lambdoid flattening; a typical compression in the malar region. This series serves a double purpose: to show that a Nordic type entered into the modern Armenian blend, and to define the Iranian variety of Nordic which may have been likewise involved in the settlement of Persia and of India.68 Furthermore, it is very similar, both metrically and morphologically, to the early Germanic cranial group, and this virtual identity draws together the two geographical extremes of an originally united family. We have seen that the Scythians and Sarmatians, although they undoubtedly included in their ranks many individuals of different political affiliations, formed nevertheless a quite constant principal racial type, which was essentially Iranian and a form of Nordic. In its characteristic low vault, as in other dimensions, it specifically resembled the earlier eastern European and central Asiatic Nordic form. It was essentially a member of the racial cluster associated with the spread of Satem Indo-European speech in both eastern Europe and Asia.

56 The sources for the historical and cultural portions of this section include Herodotus, book iv, ch. 59-75; Hippocrates, de Aere; Minns, E. H., Scythians and Greeks; Junge, J. ZFRK, vol. 3, 1936, pp. 68-77; and Win. M. McGovern's work, The Early Empires of Central Asia, which was consulted in advance of publication. 57 Donici, A., Crania Scythica, MSSR, ser. 3, Tomul X, Mem. 9, Bucharest, 1935. 58 Donici is of this opinion. He finds the same brachycephalic type in a collection of skulls from an early Moldavian monastery. 59 Debetz, G., Ann. Lab. Anth. Tb. Vovk. Acad. Sc. Ukraine, T. III, Kiev, 1930, quoted by Donici. 60 Same. 61 Jendyk, R., Kosmos, vol. 55, 1906, sec. 1-2. 62 Ivanovsky, A. (after Daniel), TILE, vol. 71, Moscow, 1891. 63 Baer, C. E. von, AFA, vol. 10, 1878, pp. 215-231. 64 Another pronouncedly Corded cranium of Scythian origin was published by Majewski, E., in Swiatowit, vol. 9, 1911, pp. 87-88. 65 Talko-Hryncewicz, J., Przyczynek do poznania, Swiata Kurhanowego Ukrainy. 66 Stolyhwo, K., Swiatowit, vol. 6, 1905, pp. 73-80. 67 Bunak, V. V., RAJ, vol. 17, 1929, pp. 64-87. 68 Unpublished series of living peoples from the mountainous regions of the northern Punjab, and the Northwest Frontier Province, which will be published by Dr. Gordon T. Bowles, conform closely to the metrical and morphological specifications of this type. |